By: Ah1Tom

On March 22, 1765, Parliament passed the Stamp Act. The Stamp Act outraged the colonists and they responded angrily with legislative protests, boycotts of British goods, and street violence. British merchants suffered financially from the American boycotts and pressured Parliament to repeal the Stamp Act. However, Parliament wanted to ensure the Colonists understood Parliament’s dominion over the American colonies and, one year later, enacted the Declaratory Act on the same day the Stamp Act was repealed, 18 March 1766. The Declaratory Act read, in part,

… parliament assembled, had, hash, and of right ought to have, full power and authority to make laws and statutes of sufficient force and validity to bind the colonies and people of America, subjects of the crown of Great Britain, in all cases whatsoever.

The American reaction to the Declaratory Act was mostly apathetic. While colonial newspapers printed the Act in full, their commentary primarily focused on repealling the Stamp Act.

Some viewed the Declaratory Act as merely a face-saving gesture, a way for Parliament to save face after retracting a flawed policy. John Dickinson likened it to “a barren tree that cast a shade over the colonies but [would] yield no fruit.”

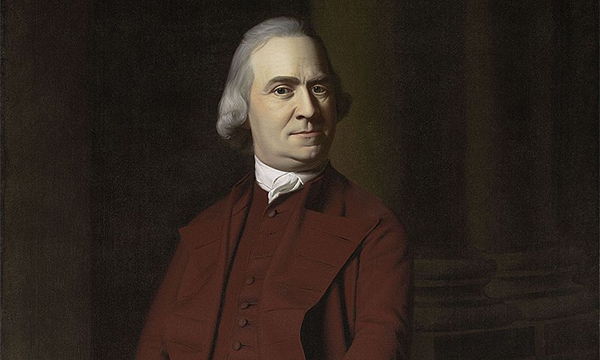

Others, however, perceived the Act as a more ominous development. Samuel Adams suggested it signaled Parliament’s intention to further tax the colonies and assert control over colonial assemblies.

In England, prominent Whig John Wilkes labeled the Declaratory Act as “the fountain from which not only waters of bitterness but rivers of blood have flowed.”

Critics like Adams pointed to a historical precedent: the 1719 Irish Declaratory Act, enacted after a land dispute and legal standoff between the English and Irish Houses of Lords. This legislation granted Parliament full authority to make laws binding Ireland, effectively nullifying the Irish legislature.

Some in the colonies feared that the 1766 Declaratory Act could be used similarly to subjugate them. Time would prove their concerns at least partially valid. Parliament’s claim of authority to govern “in all cases whatsoever” soon led to more provocative measures, including the Townshend duties, the Tea Act, and the Coercive Acts.